Sentiment analysis on tweets

What’s the mood on Twitter today? Looking at my little twitter demo from a few weeks ago (using Glide & Gaelyk on Google App Engine), I thought I could enrich the visualization with some sentiment analysis to give more color to those tweets. Fortunately, there’s a new API in Google-town, the Cloud Natural Language API (some more info in the announcement and a great post showing textual analysis of Harry Potter and New York Times)!

The brand-new Cloud Natural Language API provides three key services:

Sentiment analysis: inspects the given text and identifies the prevailing emotional opinion within the text, especially to determine a writer’s attitude as positive, negative, or neutral.

Entity recognition: inspects the given text for known entities (proper nouns such as public figures, landmarks, etc.) and returns information about those entities.

Syntax analysis: extracts linguistic information, breaking up the given text into a series of sentences and tokens (generally, word boundaries), providing further analysis on those tokens.

I’m going to focus only on the sentiment analysis in this article. When analyzing some text, the API tells you whether the content is negative, neutral or positive, returning “polarity” values ranging from -1 for negative to +1 for positive. And you also get a “magnitude”, from 0 to +Infinity to say how strong the emotions expressed are. You can read more about what polarity and magnitude mean for a more thorough understanding.

Let’s get started!

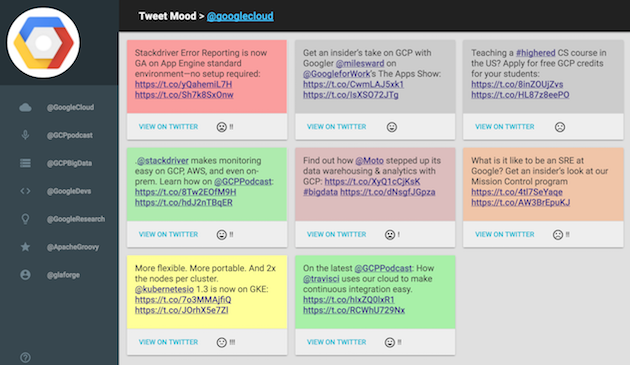

With the code base of my first article, I will add the sentiment analysis associated with the tweets I’m fetching. The idea is to come up with a colorful wall of tweets like this, with a range of colors from red for negative, to green for positive, through yellow for neutral:

I’ll create a new controller (mood.groovy) that will call the Cloud NL service, passing the text as input. I’ll take advantage of App Engine’s Memcache support to cache the calls to the service, as tweets are immutable, their sentiment won’t change. The controller will return a JSON structure to hold the result of the sentiment analysis. From the index.gtpl view template, I’ll add a bit of JavaScript and AJAX to call my newly created controller.

Setting up the dependencies

You can either use the Cloud NL REST API or the Java SDK. I decided to use the latter, essentially just to benefit from code completion in my IDE. You can have a look at the Java samples provided. I’m updating the glide.gradle file to define my dependencies, including the google-api-services-language artifact which contains the Cloud NL service. I also needed to depend on the Google API client JARs, and Guava. Here’s what my Gradle dependencies ended up looking like:

dependencies {

compile "com.google.api-client:google-api-client:1.21.0"

compile "com.google.api-client:google-api-client-appengine:1.21.0"

compile "com.google.api-client:google-api-client-servlet:1.21.0"

compile "com.google.guava:guava:19.0"

compile "com.google.apis:google-api-services-language:v1beta1-rev1-1.22.0"

compile "org.twitter4j:twitter4j-appengine:4.0.4" }

Creating a new route for the mood controller

First, let’s create a new route in _routes.groovy to point at the new controller:

post "/mood", forward: "/mood.groovy"

Coding the mood controller

Now let’s code the mood.groovy controller!

We’ll need quite a few imports for the Google API client classes, and a couple more for the Cloud Natural Language API:

import com.google.api.client.googleapis.json.GoogleJsonResponseException

import com.google.api.client.http.*

import com.google.api.client.googleapis.auth.oauth2.GoogleCredential

import com.google.api.client.googleapis.javanet.GoogleNetHttpTransport

import com.google.api.client.json.jackson2.JacksonFactory

import com.google.api.services.language.v1beta1.*

import com.google.api.services.language.v1beta1.model.*

We’re retrieving the text as a parameter, with the params map:

def text = params.txt

We’ve set up a few local variables that we’ll use for storing and returning the result of the sentiment analysis invocation:

def successOutcome = true

def reason = ""

def polarity = 0

def magnitude = 0

Let’s check if we have already got the sentiment analysis for the text parameter in Memcache:

def cachedResult = memcache[text]

If it’s in the cache, we’ll be able to return it, otherwise, it’s time to compute it:

if (!cachedResult) {

try {

// the sentiment analysis calling will be here

} catch (Throwable t) {

successOutcome = false

reason = t.message

}

}

We’re going to wrap our service call with a bit of exception handling, in case something goes wrong, we want to alert the user of what’s going on. And in lieu of the comment, we’ll add some logic to analyze the sentiment We must define the Google credentials allowing us to access the API. Rather than explaining the whole process, please follow the authentication process explained in the documentation to create an API key and a service account:

def credential = GoogleCredential.applicationDefault.createScoped(CloudNaturalLanguageAPIScopes.all())

Now we can create our Cloud Natural Language API caller:

def api = new CloudNaturalLanguageAPI.Builder(

GoogleNetHttpTransport.newTrustedTransport(),

JacksonFactory.defaultInstance,

new HttpRequestInitializer() {

void initialize(HttpRequest httpRequest) throws IOException {

credential.initialize(httpRequest)

}

})

.setApplicationName('TweetMood')

.build()

The caller requires some parameters like an HTTP transport, a JSON factory, and a request initializer that double checks that we’re allowed to make those API calls. Now that the API is set up, we can call it:

def sentimentResponse = api.documents().analyzeSentiment(

new AnalyzeSentimentRequest(document: new Document(content: text, type: "PLAIN\_TEXT"))

).execute()

We created an AnalyzeSentimentRequest, passing a Document to analyze with the text of our tweets. Finally, we execute that request. With the values from the response, we’re going to assign our polarity and magnitude variables:

polarity = sentimentResponse.documentSentiment.polarity

magnitude = sentimentResponse.documentSentiment.magnitude

Then, we’re going to store the result (successful or not) in Memcache:

cachedResult = [

success: successOutcome,

message: reason,

polarity: sentiment?.polarity ?: 0.0,

magnitude: sentiment?.magnitude ?: 0.0

]

memcache[text] = cachedResult

}

Now, we setup the JSON content type for the answer, and we can render the cachedResult map as a JSON object with the Groovy JSON builder available inside all controllers:

response.contentType = 'application/json'

json.result cachedResult

Calling our controller from the view

A bit of JavaScript & AJAX to the rescue to call the mood controller! I wanted something a bit lighter than jQuery, so I went with Zepto.js for fun. It’s pretty much the same API as jQuery anyway. Just before the end of the body, you can install Zepto from a CDN with:

<script src="https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/zepto/1.1.6/zepto.min.js"></script>

Then, we’ll open up our script tag for some coding:

<script language="javascript">

Zepto(function(z) {

// some magic here!

});

</script>

As the sentiment analysis API call doesn’t support batch requests, we’ll have to call the API for each and every tweet. So let’s iterate over each tweet:

z('.tweet').forEach(function(e, idx) {

var txt = z(e).data('text');

// ....

}

Compared to the previous article, I’ve added a data-text attribute to contain the text of the tweet, stripped from hashtags, twitter handles and links (I’ll let you use some regex magic to scratch those bits of text!).

Next, I call my mood controller, passing the trimmed text as input, and check if the response is successful:

z.post('/mood', { txt: txt }, function(resp) {

if (resp.result.success) {

// …

}

}

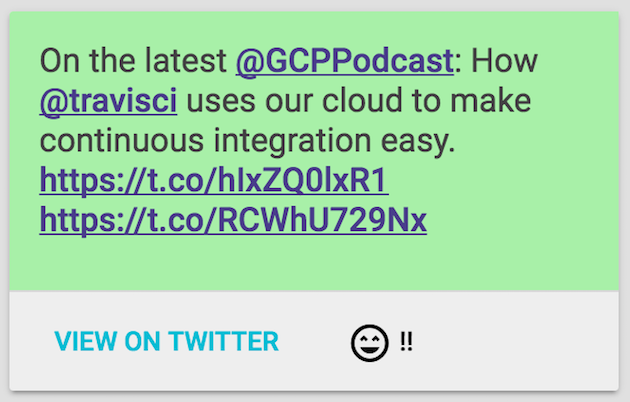

I retrieve the polarity and magnitude from the JSON payload returned by my mood controller:

var polarity = resp.result.polarity;

var magnitude = resp.result.magnitude;

Then I update the background color of my tweets with the following approach. I’m using the HSL color space: Hue, Saturation, Lightness.

The hue ranges from 0 to 360°, and for my tweets, I’m using the first third, from red / 0°, through yellow / 60°, up to green / 120° to represent the polarity, respectively with negative / -1, neutral / 0 and positive / +1.

The saturation (in percents) corresponds to the magnitude. For tweets which are small, the magnitude rarely goes beyond 1, so I simply multiply the magnitude by 100 to get percentages, and floors the results to 100% if it goes beyond.

For the lightness, I’ve got a fixed value of 80%, as 100% would always be full white!

Here’s a more explicit visualization of this color encoding with the following graph:

So what does the code looks like, with the DOM updates with Zepto?

var hsl = 'hsl(' + Math.floor((polarity + 1) \* 60) + ', ' + Math.min(Math.floor(magnitude \* 100), 100) + '%, ' + '80%) !important';

z(e).css('background-color', hsl)

.data('polarity', polarity)

.data('magnitude', magnitude);

For the fun, I’ve also added some smileys to represent five buckets of positivity / negativity (very negative, negative, neutral, positive, very positive), and from 0 to 3 exclamation marks for 4 buckets of magnitude. That’s what you see in the bottom of the tweet cards in the final screenshot:

Summary

But we’re actually done! We have our controller fetching the tweets forwarding to the view template from the last article, and we added a bit of JavaScript & AJAX to call our new mood controller, to display some fancy colors to represent the mood of our tweets, using the brand new Cloud Natural Language API.

When playing with sentiment analysis, I was generally on the same opinion regarding sentiment of the tweets, but I was sometimes surprised by the outcome. It’s hard for short bursts of text like tweets to decipher things like irony, sarcasm, etc, and a particular tweet might appear positive when reality it isn’t, and vice versa. Sentiment analysis is probably not an exact science, and you need more context to decide what’s really positive or negative.

Without even speaking of sarcasm or irony, sometimes certain tweets were deemed negative when some particular usually negative words appeared: a “no” or “not” is not necessarily negative when it’s negating something already negative, turning it into something more positive (“it’s not uncool”). For longer text, the general sentiment seems more accurate, so perhaps it’s more appropriate to use sentiment analysis in such cases than on short snippets.