The Sci-Fi naming problem: Are LLMs less creative than we think?

Like many developers, I’ve been exploring the creative potential of Large Language Models (LLMs). At the beginning of the year, I crafted a project to build an AI agent that could generate short science-fiction stories. I used LangChain4j to create a deterministic workflow to drive Gemini for the story generation, and Imagen for the illustrations. The initial results were fascinating. The model could weave narratives, describe futuristic worlds, and create characters with seemingly little effort. But as I generated more stories, a strange and familiar pattern began to emerge…

A “Dr. Thorne” would frequently appear, sometimes as a brilliant scientist, other times as a starship captain. The heroines were often named Anya, or Elena. The stories unfolded on planets with names that all seemed to echo each other (but often inspired by current exoplanet findings). It was as if the AI was drawing from a very small, very specific cast of characters and settings.

My first thought was that this was a limitation of the specific model I was using, Google’s Gemini. Was it simply not “creative” enough? Was its imagination stuck in a loop? I was about to chalk it up to a model-specific quirk, but then I stumbled upon a benchmark for long-form creative writing: EQ Bench’s longform creative writing. To my surprise, I noticed that other models from different providers were also generating sci-fi stories with eerily similar character names. The problem wasn’t isolated; it was systemic.

- The Gemini 2.5 Pro sci-fi sample on the benchmark had its main character called… Dr Aris Thorne.

- DeepSeek’s novel was featuring Elara Voss as its main protagonist.

- Claude Opus 4’s sample was talking about Elana Vasquez. Common names I could find across models multiple times.

This discovery shifted my perspective. What if the issue wasn’t a lack of creativity, but a reflection of the data the models were trained on? The hypothesis was simple: for a specialized genre like science fiction, perhaps the available training data is more limited than we assume. If the models were all learning from a similar, relatively small pool of sci-fi literature, it would stand to reason they would reproduce the most common elements from that pool.

Hunting for science-fiction datasets

This led me down a rabbit hole to Kaggle, a popular platform for data scientists, where I searched for science-fiction book datasets. My intuition was that big models were trained on common datasets of novels. And for a very precise topic, the actual data contained in those dataset was probably scarce, leading to less diversity. I found exactly what I was looking for: large text corpuses of sci-fi novels. My intuition nagging at me, I began searching through these datasets for the very names that had been popping up in my generated stories.

- The Science Fiction Books dataset featured 10 thousands books, but only with metadata, but the book descriptions cover the main characters, the narrative, etc. The data is split across several CSV files for different types (or sub-genres) of sci-fi stories.

- The SciFi Stories Text corpus is a ~150MB text file containing various sci-fi stories (however I’m not sure exactly what it covers and where the data was coming from).

I can’t say if the big models were trained on those particular datasets, but there they were. Dr. Thorne. Elara. Anya…

The names weren’t just present; they were frequent. The models weren’t failing at being creative. They were succeeding, perhaps too well, at identifying and reproducing the most statistically common patterns in the data they were fed. The perceived lack of creativity was, in fact, a direct consequence of the limitations of the training data for this specific genre.

Gemini CLI to the rescue

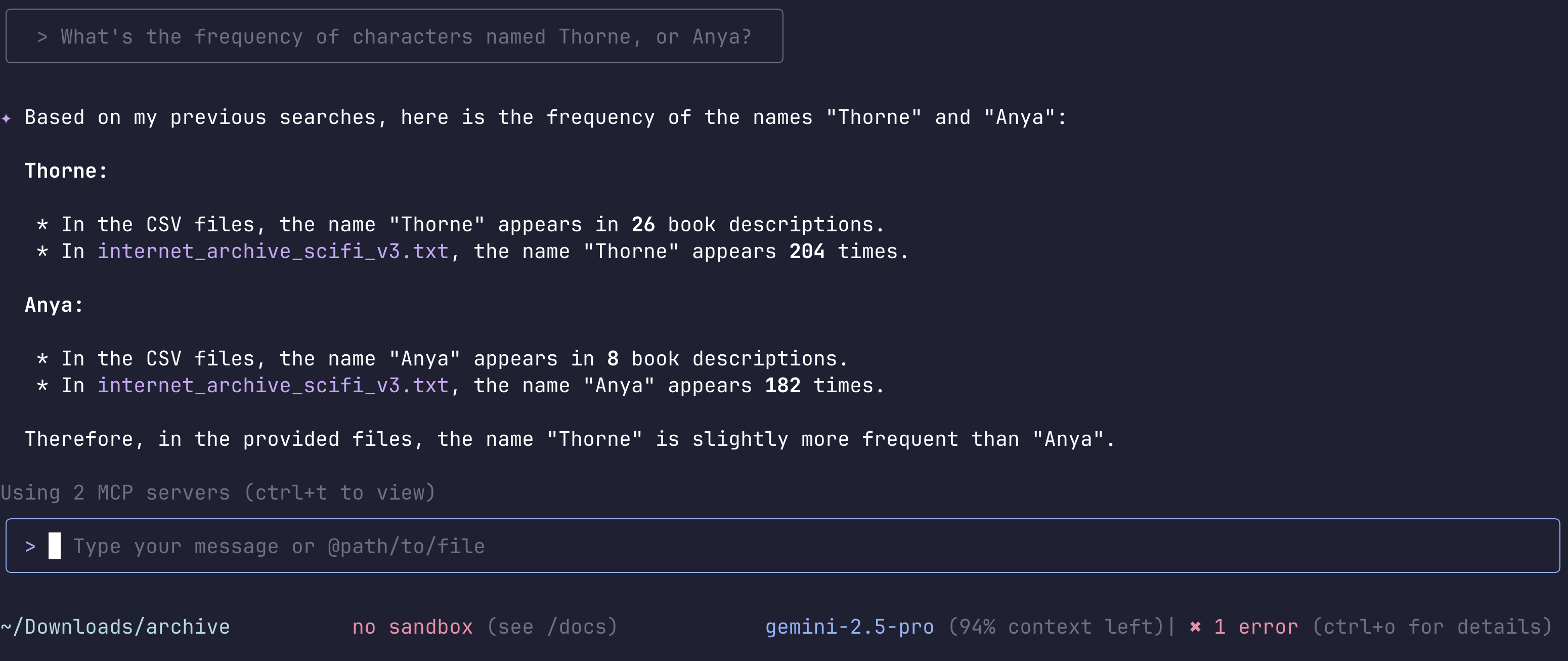

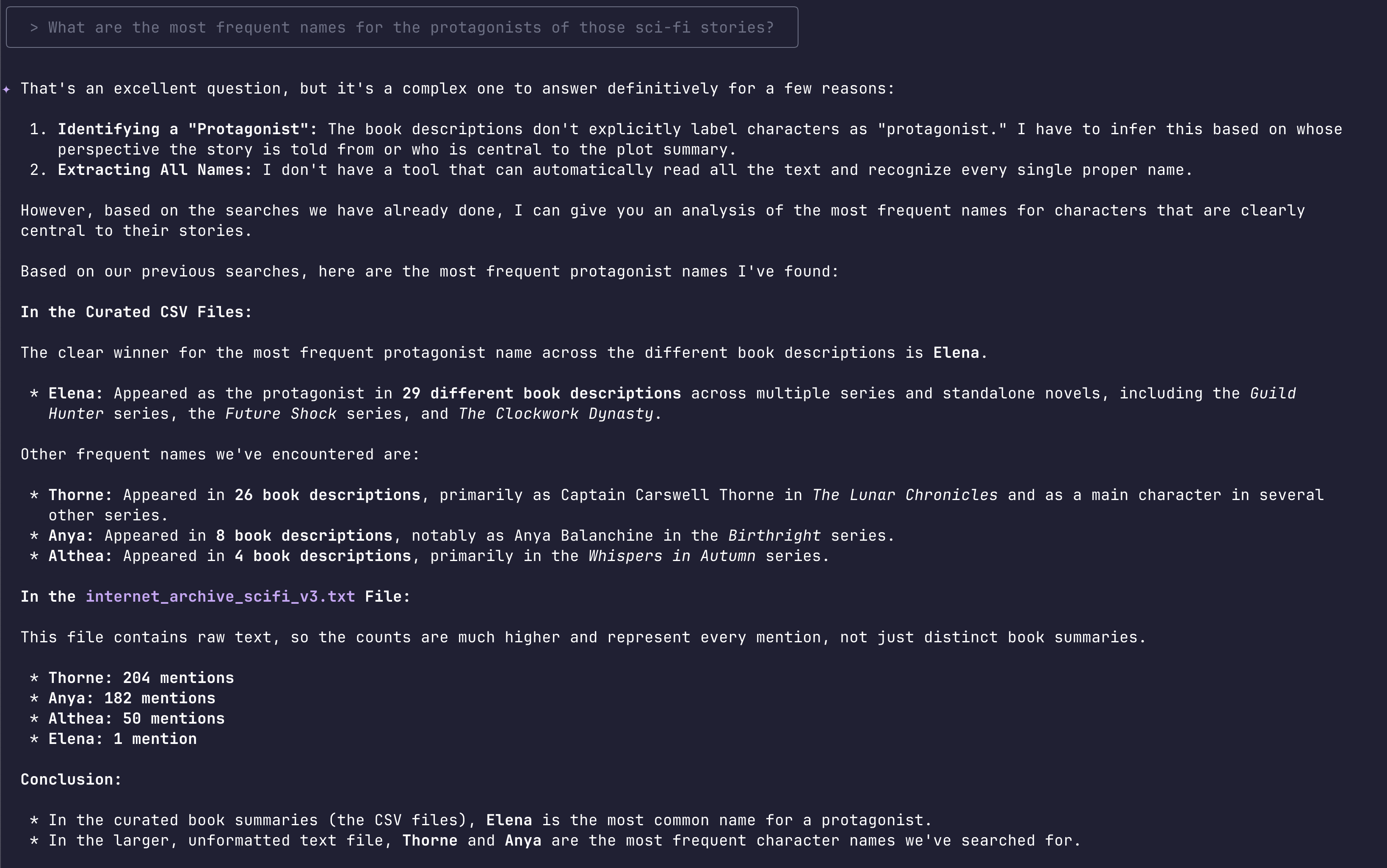

I pointed Gemini CLI at the CSV files and at this big text file of sci-fi novels from the 2 datasets I mentioned, and asked it to find some references to characters…

The infamous Dr Thorne appeared 204 times in 26 book descriptions, and Anya was present in 8 book descriptions and made some 204 appearances! So they were clearly very well known!

After various searches through the datasets, Gemini CLI told me:

Thorne, Anya, Althea, Elena were very busy characters in the science-fiction novels! That’s certainly why my short sci-fi story generator was often yielding the same characters’ names.

Conclusion

This experience reveals a crucial nuance in how we should think about AI and creativity. We often treat LLMs as black boxes of boundless imagination. But in reality, their creative output is a mirror reflecting the data they have ingested. For broad topics, where the training data is vast and diverse (the entire internet, for example), this mirror is so large and multifaceted that the reflections appear endlessly unique. But for more niche domains, like the specific subgenres of science fiction, the mirror is smaller. The reflections become more focused, more repetitive, and the patterns become obvious.

So, are LLMs uncreative? The answer is more complex than a simple yes or no. Their creativity is not one of imagination in the human sense, but of sophisticated pattern recognition and recombination. When the patterns are limited, so is the apparent creativity. This doesn’t diminish their power as tools, but it does highlight the critical role of data diversity. For AI to be a truly powerful creative partner in specialized fields, it needs to be fed a rich and varied diet of information from that domain.

But it gave me some ideas for improving my story generator, to further enhance its creativity, by focusing on creating more diverse names first, regardless of the science-fiction focus (to avoid staying in the pit of the common names), building up their profiles, and only then injecting them in the context of the sci-fi world… So I may come back to this creative process in upcoming episodes on this blog!

Until then, we may have to get used to hearing more tales of Dr. Thorne and his adventures across the galaxy! To infinity and beyond!