Researching Topics in the Age of AI — Rock-Solid Webhooks Case Study

Back in 2019, I spent significant time researching Webhooks. In particular, I was interested in best practices, pitfalls, design patterns, and approaches for implementing Webhooks in a reliable, resilient, and effective way.

Everything is distilled in that article: Implementing Webhooks, not as trivial as it may seem

It likely took me a full week to dive deep into this subject, finding sources and experimenting with design patterns myself. But nowadays, AI makes it easier to dive deeper into topics, explore unfamiliar aspects, and share findings with your team.

As I built a research agent based on Google’s Deep Research agent, I wanted to see how far it’d go with a topic I had covered a while ago.

Armed with my custom research agent

(via the Javelit frontend I built around it),

I entered the query: Webhook best practices for rock solid and resilient deployments.

Gemini 3 Flash gave me a list of topics associated with that theme, and I selected the following ones:

- Cryptographic signature verification using HMAC-SHA256

- Implementing idempotency keys to prevent duplicate event processing

- Asynchronous processing architectures using message queues and background workers

- Preventing replay attacks with timestamp validation and nonces

- Retry strategies using exponential backoff with jitter

- Dead letter queue (DLQ) implementation and management for failed deliveries

- Security through Mutual TLS (mTLS) and IP allowlisting

- Webhook payload versioning and backward compatibility strategies

- Handling high-volume event bursts with rate limiting and buffering

- Circuit breaker patterns to protect downstream services from failure

- Schema validation and data minimization in webhook payloads

There’s significant overlap with the topics I covered in my old presentation! I talked about idempotency, signatures, dead-letter queues, IP allowlisting, rate limiting & buffering, etc. This validates my previous findings and shows that today’s generative AI capabilities can identify the same key topics.

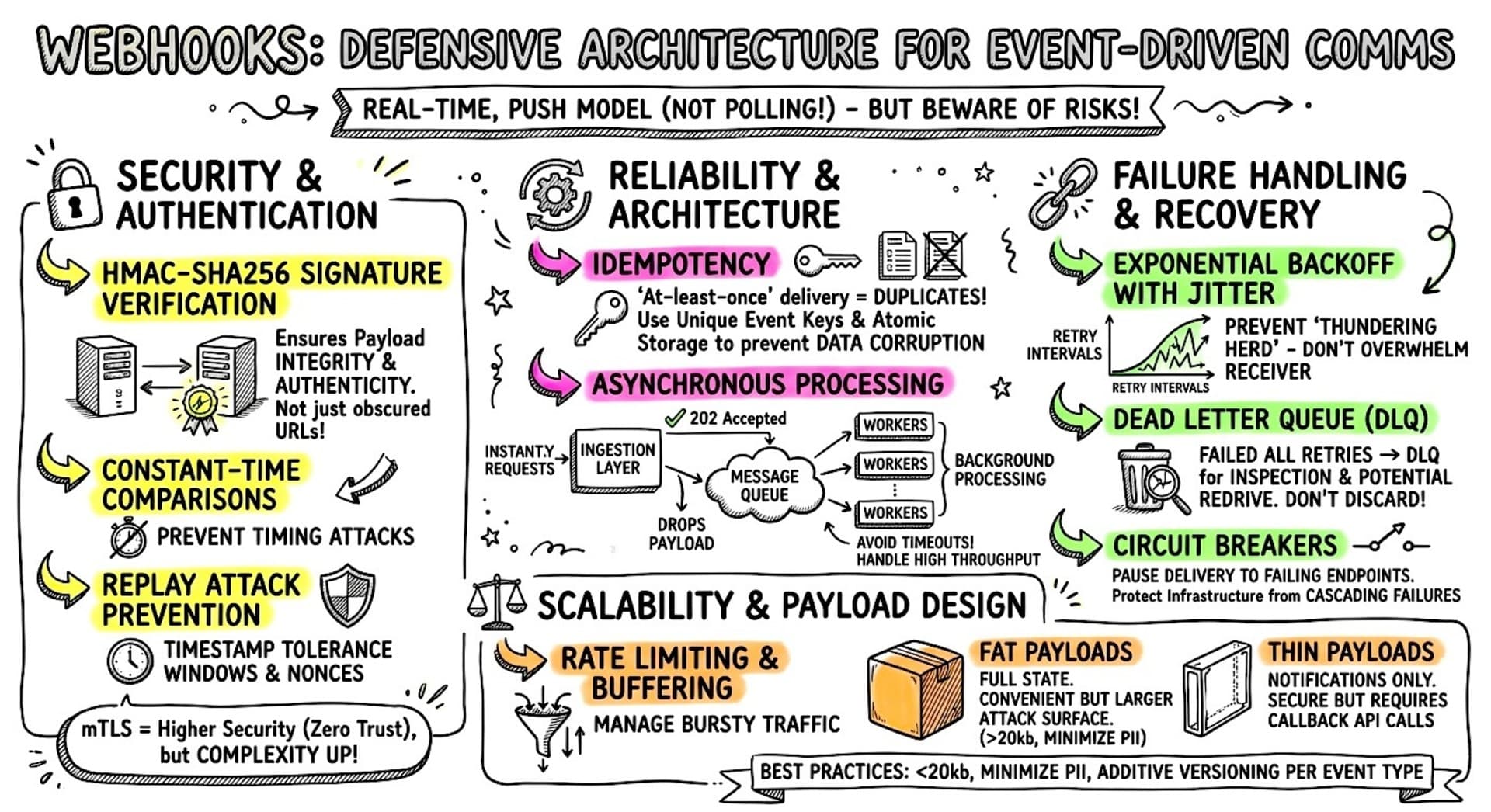

So I let Deep Research explore those topics. After a few minutes, my agent wrote a long report in a concise style (I used prompts to steer the report generation toward concise writing and avoid “AI Slop”). Then Gemini 3 Pro created a summary, and Nano Banana Pro generated a sketchnote illustration.

Let’s start with the illustration (the same you saw as the banner for this post):

Infographics

I have a special prompt to generate such sketchnotes, which I find readable, and appealing to share on social media:

Create a hand-drawn and hand-written sketchnote style

summary infographic, with a pure white background,

use fluo highlighters for the key points,

about the following information: ...

And I pass the summary generated by Gemini 3 Pro below.

Summary

The summary is generated via this prompt, passing the entire research:

Create a concise summary of the research below.

Go straight to the summary; don't introduce it

(don't write "Here's a summary..." or equivalent).

For this research on Webhooks, here’s what the summary was. The summary’s structure also guided the organization of the sketchnote above:

Webhooks facilitate real-time, event-driven communication between systems but require a defensive architecture to ensure security, reliability, and scalability. Unlike polling, webhooks utilize a “push” model, necessitating robust handling of network partitions, malicious activity, and traffic spikes.

Security and Authentication Security implementation must go beyond obscured URLs. The industry standard involves HMAC-SHA256 signature verification to ensure payload integrity and authenticity. Critical implementation details include using constant-time string comparisons to prevent timing attacks and validating raw, unparsed payloads. To prevent replay attacks, systems should enforce timestamp tolerance windows and utilize nonces. While Mutual TLS (mTLS) offers a higher security standard for zero-trust environments, it introduces significant complexity compared to signatures and IP allowlisting.

Reliability and Architecture Because webhooks typically guarantee “at-least-once” delivery, receivers must implement idempotency using unique event keys and atomic storage to prevent duplicate processing from corrupting data. To handle high throughput and avoid timeouts, architectures should be asynchronous: an ingestion layer should immediately acknowledge requests (returning 202 Accepted) and offload the payload to a message queue for background processing by workers.

Failure Handling and Recovery Robust systems employ exponential backoff with jitter for retries to prevent “thundering herd” scenarios that could overwhelm the receiver. Messages that fail all retry attempts should be routed to a Dead Letter Queue (DLQ) for inspection and potential redrive rather than being discarded. Additionally, circuit breakers are essential to pause delivery to failing endpoints, protecting the infrastructure from cascading failures during outages.

Scalability and Payload Design To manage bursty traffic, providers should enforce rate limiting and buffering. Payload design involves a trade-off between “Fat” payloads (full state, convenient but larger attack surface) and “Thin” payloads (notifications only, secure but require callback API calls). Best practices suggest keeping payloads under 20kb, minimizing PII, and utilizing additive versioning per event type to maintain backward compatibility.

Even just the summary, as is, is already valuable when researching a subject, as it gives you all the key pointers to go further.

Generating a Slide Deck

I delivered my Webhook talk at a handful of conferences in Europe. And of course, I needed a slide deck! I often spend significant time on my decks, as I want them to be polished, clear, and beautiful. Usually, I try to reduce the amount of text in favor of visual representations like diagrams and photographic illustrations.

Right, so I have a report and an infographic, but what about the deck? My agent doesn’t (yet?) handle that, so instead, I turned to NotebookLM, gave it my research, and asked it to generate a slide deck with a particular design:

A slide deck for a technical audience, describing all the best practices to implement rock solid resilient webhooks. Opt for a blueprint architectural style, with illustrations.

And it complied, generating the following deck, which I could see myself presenting:

The style is consistent across the deck and quite beautiful. I usually put less text on slides, but it works here. Under the hood, NotebookLM uses 🍌 Nano Banana Pro (aka Gemini 3 Pro Image), and the included graphics look spot on, sharp, and accurate. I didn’t even spot typos in the generated text.

Going Further: Should I share those?

More and more I use AI in my work, but I still prefer writing my articles by hand. I can use generative AI to do a first draft, explain a piece of code, or come up with a conclusion. I also use image generation to create either illustrations or sketchnotes. But otherwise, it’s still me. My writing, my design, my style, my authentic voice.

What I’m wondering though is what to do with such research reports. I run such reports to explore a particular topic, to avoid forgetting some key angle or aspect. But I usually keep that research for me (sometimes saved inside my Obsidian vault, or as Google Docs here and there)

This week, I had a nice lunch with a couple old friends who were thinking that it was worth sharing those reports more widely, rather than keeping them private (one of my friend was sharing his research publicly in a GitHub repository.)

On the one hand, I don’t want to increase the quantity of AI slop available on the internet, but on the other hand, once they’re generated, it’s sad to see all those tokens wasted, and benefiting me exclusively! I would clearly label them as AI generated research reports or similar though, but maybe others would find those useful and interesting?

I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on this! Don’t hesitate to share them with me on social media.

Generative AI, assisted with agents that do targeted web searches, really changes the game in terms of research. Tools like NotebookLM are able to find the right sources of information, and can generate all sorts of artifacts and visualisations (audio and video podcasts, mindmaps, infographics, quizes, etc.) And image models like 🍌 Nano Banana are incredible and able to generate very clear visuals. This is really an interesting era to learn more about any topics, and at a much greater depth than scouring your favorite search engine manually! Deep Research and NotebookLM give you the URLs of the sources, so you can double check the accuracy of the reference material.

For the curious, here’s the full research report below, that my agent crafted about rock-solid webhooks:

Click to view the full generated report on Webhooks

Webhook Implementation Best Practices: Security, Reliability, and Scalability

Key Points

- Security is Paramount: Relying solely on obscure URLs is insufficient; implementation must include cryptographic signing (HMAC-SHA256) to ensure integrity and authenticity, alongside HTTPS for confidentiality.

- Reliability through Idempotency: Because webhooks typically guarantee “at-least-once” delivery, receivers must implement idempotency keys to safely handle duplicate requests without corrupting data state.

- Asynchronous Architecture: Decoupling ingestion from processing using message queues is critical for handling traffic bursts and preventing timeout failures at the ingress point.

- Failure Mitigation: Robust systems employ exponential backoff with jitter for retries to prevent “thundering herd” scenarios, utilizing Dead Letter Queues (DLQs) for effectively managing permanently failed messages.

- Traffic Management: Circuit breakers and rate limiting are essential to protect both the sender and receiver infrastructure from cascading failures during high-load events or outages.

Introduction

Webhooks represent the standard for event-driven communication between distributed systems, allowing platforms to notify downstream services of state changes in real-time. Unlike polling, which is resource-intensive and suffers from latency, webhooks enable a “push” model where data is transmitted immediately upon event occurrence. However, this architectural shift introduces significant challenges regarding security, reliability, and scalability. A production-grade webhook implementation requires a rigorous adherence to defensive design patterns to handle network partition, malicious actors, and extreme volume spikes.

This report synthesizes best practices across security verification, architectural decoupling, failure recovery, and payload design. It serves as a comprehensive guide for engineering teams aiming to build or consume resilient webhook systems that function reliably at scale.

1. Cryptographic Security and Authentication

The public exposure of webhook endpoints makes them susceptible to impersonation, tampering, and man-in-the-middle attacks. Security must be implemented in layers, primarily focusing on transport security and payload verification.

1.1 HMAC-SHA256 Signature Verification

The industry standard for authenticating webhook payloads is the Hash-based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) using the SHA-256 algorithm. This mechanism allows the receiver to verify that the payload was generated by the expected sender and has not been modified in transit 1, 2.

Mechanism of Action:

- Shared Secret: A secret key is exchanged between the webhook provider and the consumer. This key is never transmitted over the network but is stored securely (e.g., in a Key Management Service) 2, 3.

- Hashing: The provider computes a hash of the payload body using the shared secret and the SHA-256 algorithm.

- Transmission: This hash is included in the HTTP headers (e.g., X-Signature or X-Hub-Signature-256) sent with the POST request 4.

- Verification: Upon receipt, the consumer independently computes the hash of the raw payload using their copy of the secret and compares it to the header value 5, 6.

Implementation Criticalities:

- Constant-Time Comparison: When comparing the calculated signature with the received signature, developers must use a constant-time string comparison function. Standard string comparison returns false as soon as a mismatch is found, which exposes the system to timing attacks where an attacker can deduce the signature character by character based on response time 3, 6.

- Raw Payload Access: Verification must be performed on the raw, unparsed request body. Frameworks that automatically parse JSON before verification can alter whitespace or field ordering, causing hash mismatches 3, 6.

- Key Rotation: Security best practices dictate the ability to rotate secrets without downtime. This is achieved by supporting multiple active keys during a transition period or using a Key-ID header to indicate which secret was used for signing 1, 2.

1.2 Mutual TLS (mTLS)

While HTTPS ensures encryption in transit, Mutual TLS (mTLS) provides a higher level of authentication by requiring both the client (webhook sender) and the server (webhook receiver) to present valid x.509 certificates during the TLS handshake 4, 7.

Advantages and Trade-offs: mTLS aligns with Zero Trust security principles, ensuring that traffic is trusted in both directions at the transport layer before any application logic is invoked 7, 8. It effectively mitigates spoofing and man-in-the-middle attacks. However, it introduces significant operational complexity regarding certificate management, issuance, and rotation 7, 8. For many use cases, mTLS is considered overkill compared to HMAC, but it remains the gold standard for high-security environments like banking or healthcare 8.

1.3 IP Allowlisting

Restricting webhook traffic to a specific list of IP addresses (allowlisting) is a common defense-in-depth strategy. By blocking all traffic not originating from known provider IPs, the attack surface is reduced 9, 10.

Limitations in Modern Architectures: IP allowlisting is increasingly difficult to maintain in cloud-native environments where providers use dynamic IP ranges or serverless infrastructure 11. It creates a maintenance burden where the consumer must manually update firewall rules whenever the provider expands their infrastructure 12, 13. Consequently, IP allowlisting should be treated as a supplementary measure rather than a primary authentication method 3, 13.

1.4 Preventing Replay Attacks

A replay attack occurs when an attacker intercepts a valid, signed webhook request and resends it to the endpoint to duplicate an action (e.g., forcing a second payment).

Timestamp Validation: To prevent this, the signature header should include a timestamp. The receiver verifies that the timestamp is within a strictly defined tolerance window (e.g., 5 minutes) relative to the system time 6, 14. If the request is too old, it is rejected, even if the signature is valid. Including the timestamp in the signed payload ensures the attacker cannot modify the time to bypass the check 14.

Nonce Implementation: For stronger protection, a unique “nonce” (number used once) or unique request ID can be included. The receiver stores processed nonces in a fast lookup store (like Redis) with a Time-To-Live (TTL) matching the replay window. If a nonce is seen a second time, the request is rejected 6.

2. Reliability and Data Integrity

Distributed systems cannot guarantee “exactly-once” delivery due to network acknowledgments potentially failing after processing. Therefore, webhook systems almost universally operate on an “at-least-once” delivery model, necessitating robust handling of duplicate events.

2.1 Idempotency Implementation

Idempotency ensures that performing the same operation multiple times produces the same result as performing it once. This is the primary defense against data corruption caused by webhook retries 15, 16.

Idempotency Keys: Providers should include a unique identifier (Idempotency Key or event_id) in the webhook headers or payload 16, 17. The receiver uses this key to lock processing for that specific event.

- Deduplication Store: A fast, atomic store (e.g., Redis) checks if the key has been processed. Using atomic operations like SETNX (Set if Not Exists) prevents race conditions where two parallel requests for the same event might both proceed 16.

- Retention Window: The keys should be stored for a duration exceeding the maximum retry window of the provider (typically 24 to 72 hours) 18.

- Transactional Upserts: In database operations, using “upsert” logic (update if exists, insert if new) based on the unique event ID ensures consistency at the database level 16.

2.2 Asynchronous Processing Architectures

Synchronous processing of webhooks—where the receiver executes business logic before returning an HTTP response—is a major anti-pattern. It couples the provider’s availability to the consumer’s processing speed and risks timeouts 15, 16.

Queue-Based Decoupling: The recommended architecture involves an ingestion layer that does nothing but authenticate the request, push the payload to a message queue (e.g., RabbitMQ, Kafka, SQS), and immediately return a 202 Accepted status 19, 20, 21.

- Benefits: This ensures that the ingestion layer can handle high throughput without waiting for slow downstream processes (e.g., generating PDFs, sending emails) 22, 23.

- Worker Pattern: Background workers pull messages from the queue to process them. If a worker fails, the message remains in the queue or is moved to a retry queue, ensuring no data is lost during application crashes 20, 24.

- Buffering: This architecture acts as a buffer (shock absorber) during traffic spikes, allowing the system to “hold the load” and process it at a manageable rate rather than crashing the web server 23.

3. Failure Handling and Recovery

Failures in webhook delivery are inevitable due to network blips, downtime, or bugs. A robust system must distinguish between transient and permanent failures and handle each appropriately.

3.1 Retry Strategies: Exponential Backoff and Jitter

When a webhook delivery fails (e.g., receiver returns 500 or times out), the provider must retry. However, immediate retries can worsen the issue, especially if the receiver is overloaded.

Exponential Backoff: This algorithm increases the wait time between retries exponentially (e.g., 1s, 2s, 4s, 8s). This gives the failing system “breathing room” to recover 25, 26.

- Formula: 25.

- Capping: A maximum delay (e.g., 1 hour) prevents retry intervals from becoming unreasonably long 25.

Jitter: Exponential backoff alone can lead to the “Thundering Herd” problem, where multiple failed webhooks retry at the exact same synchronized times, creating repeated spikes of traffic. “Jitter” adds randomness to the backoff interval to desynchronize these retries 25, 27.

3.2 Dead Letter Queues (DLQ)

If a message fails to deliver after all retry attempts are exhausted, it should not be discarded. Instead, it must be moved to a Dead Letter Queue (DLQ) 19, 26, 28.

- Purpose: The DLQ acts as a holding area for “poison messages” or permanently failed deliveries. This prevents the retry queue from being clogged with unprocessable events 17.

- Management: Systems must provide tooling to inspect DLQ messages, determine the root cause (e.g., bug in consumer code), and “redrive” (replay) them once the issue is fixed 18, 29.

- Alerting: The size of the DLQ is a critical metric; growing DLQ depth should trigger alerts for manual intervention 17, 19.

3.3 Circuit Breaker Pattern

While retries handle individual message failures, the Circuit Breaker pattern protects the entire ecosystem from total collapse during prolonged outages 30, 31.

Functionality: If a specific endpoint fails a significant percentage of requests (e.g., 100 failures in 60 seconds), the circuit breaker “trips” to an Open state.

- Open State: Delivery is paused entirely for that endpoint. The provider stops wasting resources trying to send requests that will likely fail 31, 32.

- Half-Open State: After a cooldown period, the system allows a limited number of “test” requests. If these succeed, the circuit closes and normal flow resumes. If they fail, it re-opens 31.

- Distributed State: In large systems, the state of the circuit breaker is often managed in a distributed store like Etcd or Redis to synchronize awareness across all delivery nodes 33.

4. Scalability and Payload Design

As systems grow, the volume and complexity of webhook events increase. Proper design choices in payloads and traffic management are essential for long-term maintainability.

4.1 Handling High-Volume Bursts

Webhook traffic is rarely uniform; it is “bursty” by nature (e.g., bulk updates triggering thousands of events) 23, 34.

Rate Limiting: Providers should enforce rate limits on outgoing webhooks to prevent overwhelming consumer endpoints. This smoothens traffic spikes into a consistent stream 35. If the limit is reached, requests are throttled or queued rather than dropped 35.

Buffering: For self-hosted solutions, an intermediate buffering layer (like NGINX or a lightweight “Holding the Load” service) can accept connections rapidly and persist requests to storage before they reach the heavier application logic 23, 36.

4.2 Payload Design: Fat vs. Thin Events

The content of the webhook payload involves a trade-off between efficiency and coupling.

- Fat Payloads (Event-Carried State Transfer): The payload contains the full resource state (e.g., the complete Order object).

- Thin Payloads (Event Notification): The payload contains minimal data, typically just the event type and resource ID (e.g., {“event”: “order.created”, “id”: “123”}).

- Best Practice: Many systems use a hybrid or offer “Thin” events by default for security, with optional expansion for trusted internal consumers 39. Ideally, keep payloads under 20kb to reduce transmission overhead 42.

4.3 Schema Validation and Versioning

Webhook payloads constitute an API contract. Breaking changes (removing fields, changing types) can cause downstream failures.

Versioning:

- Event-Type Versioning: Versioning is best applied per event type (e.g., v2.invoice.paid vs invoice.paid) rather than a global API version, as this allows granular evolution 43.

- Additive Changes: Schema evolution should be additive (adding new fields is safe; removing fields is breaking). Deprecation periods are required for removing fields 21.

Validation: Consumers should validate incoming payloads against a JSON Schema to fail fast if the data structure is malformed 44, 45. However, validation logic should be permissive (“tolerant reader” pattern)—ignoring unknown fields to maintain forward compatibility 21.

Data Minimization: To comply with privacy regulations (GDPR, CCPA), payloads should minimize Personal Identifiable Information (PII). Sensitive data should preferably be retrieved via a secure API call (Thin Payload) rather than broadcasted in the webhook 6, 14, 41.

Conclusion

Implementing a robust webhook system requires a holistic approach that balances security, reliability, and efficiency. By securing the transport with HMAC and mTLS, ensuring reliability through idempotency and retries, and designing for scale with asynchronous queues and circuit breakers, developers can build event-driven architectures that are resilient to the chaotic nature of distributed networks. The separation of concerns—where the ingestion layer strictly handles intake and the worker layer handles processing—remains the fundamental architectural pattern for successful high-volume webhook implementations.

Sources:

- ngrok.com

- medium.com

- loginradius.com

- stytch.com

- dev.to

- webflow.com

- webhooks.fyi

- latenode.com

- security.com

- webhookrelay.com

- techradar.com

- dev.to

- hookdeck.com

- snyk.io

- hookdeck.com

- medium.com

- medium.com

- medium.com

- hookdeck.com

- dev.to

- medium.com

- youtube.com

- dev.to

- medium.com

- hookdeck.com

- svix.com

- latenode.com

- amazon.com

- integrate.io

- medium.com

- mambu.com

- stackoverflow.com

- raymondtukpe.com

- hookdeck.com

- trackunit.com

- medium.com

- codesimple.blog

- codeopinion.com

- brianlovin.com

- hookdeck.com

- mendix.com

- github.com

- svix.com

- inventivehq.com

- zuplo.com